However, the dilemma we are facing today is not a small one. Most of us are all too aware that the American church today is in many ways floundering, struggling to produce a robust and deep kind of spirituality that affects change in us and in our communities, and it has lost much credibility and relevance in the public eye. Not many are coming into the church. More are leaving. So many of our current forms of church were created in the 1950’s, but that world no longer exists. So we are looking for new wineskins, new practices, new worldviews where our faith can be contextualized today. And this has been the point of this discussion - what is actually good news to our neighbor, our co-worker, or our classmate? Most of us experience incongruence or a gap between what we see in Jesus and scripture and our own lived experience. I know I do. I’m not sure I even have language to share the wonder of who Jesus is to me in a way that connects. And so what does good news look like? What are the practices we will live out to see our neighbors experience the transforming love of God?

This will be the first of a series of posts about St. Patrick, Celtic Christianity and church in the neighborhood. For Saint Patrick faced similar dilemmas of his day in a time where much of the world was deemed “barbarian” and thus beyond the power of the gospel. And yet as you will hear, his mission led to a wide sweeping movement of the Spirit among the Celtic tribes of Ireland, Scotland, England and beyond. Saint Patrick grew up in what is now northeast England around 400 AD, belonging to the “Britons”, a Celtic tribe, yet “Romanized” culturally under Roman occupation. He grew up Christian, but it was said that Patrick was a rather nominal one, known to be a bit of a wild youth. When Patrick was 16, a band of Celtic pirates invaded his homeland. Yes, this story is dramatic - think Pirates of the Caribbean - or what today are the horrors of the slave trade. They captured Patrick along with many other young men, forced them on a ship to Ireland and sold them into slavery. Patrick then spent the next 6 years enslaved to a landowner where he began to understand the culture of the Irish Celtic from the underside. And as he herded cattle day after day, God revealed himself to Patrick through the natural revelation of beauty and nature. Then one night in a dream, Patrick was told that a ship would be waiting for him on the coastline and he obeyed this prompting and escaped slavery, returning eventually home to England. Now as a changed man devoted to the call of God on his life, he began to train for the priesthood. Another night many years later, Patrick had a second dream that changed his life again. He referred to it as his Macedonian Call to bring the gospel back to his former captors, the Irish Celtic people. And so Patrick became the first missionary bishop to Ireland.

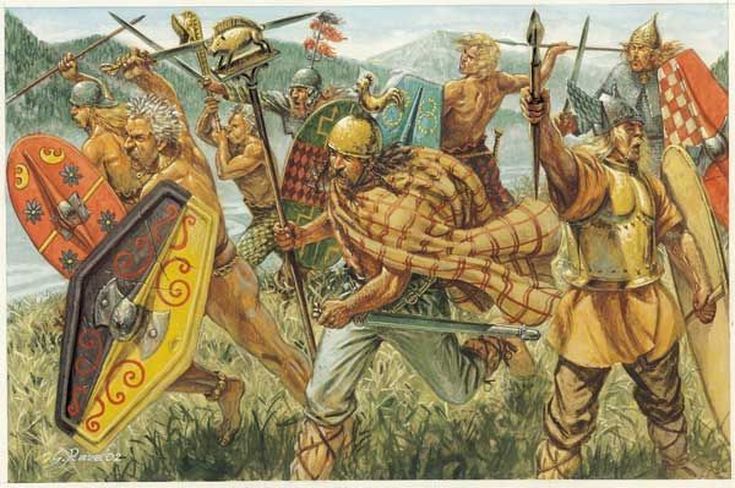

So this was pretty extraordinary. Patrick’s mission to Ireland was such an unprecedented undertaking that it is impossible to overstate its significance or the magnitude of the challenge they faced. You see, the Irish Celtics were thought to be “barbarians” -- for the Romans basically categorized everyone who wasn’t Roman or those they perceived as “illiterate” or “uncivilized” as barbarians. And the Roman Church, not unlike our more recent history of protestant mission, was concerned with two things: Christianizing and civilizing. [We now use the term colonizing.] And it was believed then that civilizing had to come first before a people could be Christianized. Today we too see many barriers for people to enter “Christian Culture”. However, what was believed to be impossible became a reality as new imaginations were forged and a new paradigm for mission emerged.

Sound familiar? Jesus too was accused of such things. In Mark 2, Jesus and his disciples were dining with the barbarians of their day, their posse of tax collectors and sinners; and it says there was a whole band of them, for many followed Him. When the Pharisees saw that He was eating with the “barbarians”, they said to His disciples, "Why is He eating and drinking with tax collectors and sinners?" And hearing this, Jesus said to them, "It is not those who are healthy who need a physician, but those who are sick; I did not come to call the righteous, but sinners." And we see this truth throughout the gospels: that Jesus did, in fact, come for the barbarian -- the lost, the broken, the poor and the oppressed. Likewise, isn’t this our call as well? I hope someday to be lucky enough to be criticized for hanging out with the wrong folks.

It is important to note that none of this ruffian lot were even welcome in the Temple. They couldn’t have come to church on a Sunday morning if they tried! And so we see Jesus redefining the game. Just as St. Patrick did. [And I would add we must too.] And it begs the question, who are the barbarians today? Of course, I don’t like to use this word as obviously the unchurched are not in fact barbarian at all, but fellow brothers and sisters, bearing the image of the divine. However, it does perhaps effectively carry the shock value necessary to awaken us to our distorted thinking. Who are those who would never darken the door of a church? Not surprisingly these days, this is quite an easy question. Most of us know plenty of people that would never come to church on a Sunday morning. And yet, have we written them off? Do we view them as unreachable? And what of our gospel? Do we think it irrelevant? Lacking the power to affect change our communities? I think the point that we must make is to the nature of Patrick’s call which is similar to that of Jesus'. Which was not to the status quo. Not to the Church as it was. Not to the well traveled paths and traditions. But to the Barbarian. The unchurched [which is the majority of Seattle today]. And new paths. And if Jesus was called to those who were not included in “church” in his day, I have to believe this is our call as well.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed