Does the gospel of Jesus Christ transform culture? Many Christians today believe in a gospel that transforms the soul but not society. This question then lies at the heart of a Christian’s socio-political understanding. For me, it is a resounding “yes.”

For if the arc of scripture begins with the goodness and shalom of Creation and ends with its restoration in New Creation, then it follows that we are to be participants in this work of transformation. “Can the conclusion be avoided that not only is shalom God’s cause in the world but that all who believe in Jesus will, along with him, engage in the works of shalom? Shalom is both God’s cause in the world and our human calling.”[1] Shalom is the underpinning for a socio-political understanding that seeks human flourishing, justice, and right relationships with God, self, neighbor, and creation. This vision of human happiness and wholeness found in the inseparable love of God and neighbor informs my belief in a Christ who transforms culture.

Ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr’s models for Christ and Culture prove helpful here. [2] Two of the most predominant approaches today hold moral weight, Christ Against Culture and Christ Of Culture. The former offers a faith deeply committed to preserving holiness and a counter-cultural life. The latter offers an engagement with culture and an ability to contextualize faith in the language and forms of the day. Yet, one without the other offers a misshapen gospel. I believe that Christ Transforming Culture demonstrates an incarnational model that holds these two together — in love of God and neighbor, piety and justice, love incarnate in the neighborhood for the flourishing of all. We need a "radical evangelicalism [that] offers a tradition and a trajectory that is biblically based, Christ-centered, and socially involved—a gospel that embraces forgiveness and holiness for individuals and redemption and wholeness for the world." [3]

It is a travesty that piety has been separated from justice in the sociopolitical sphere. For politics is nothing more than the interrelationships between people and how power is shared, a realm ripe for the preservation of salt, liberation from oppression, and restoration of communities.[4] This kingdom liberation does not locate itself in the kingdoms and empires of this world – either in confusing God’s kingdom with a political agenda or in hopes of gaining worldly power or dominion. Rather, it is located once again in the justice and shalom of “right relationship” or “righteousness.” It is in the explicit call of scripture to care for the most vulnerable and needy in our communities, “not in rights asserted against one another” [5] but in responsibilities of humanity’s covenantal bond and “inescapable mutuality.”[6] Faith without works is dead, and a religion that has largely failed to address the injustices of our times is an impotent one. “Christians have not done enough in this area of conversion to the neighbor, to social justice, to history. They have not perceived clearly enough yet that to know God is to do justice.” [7]

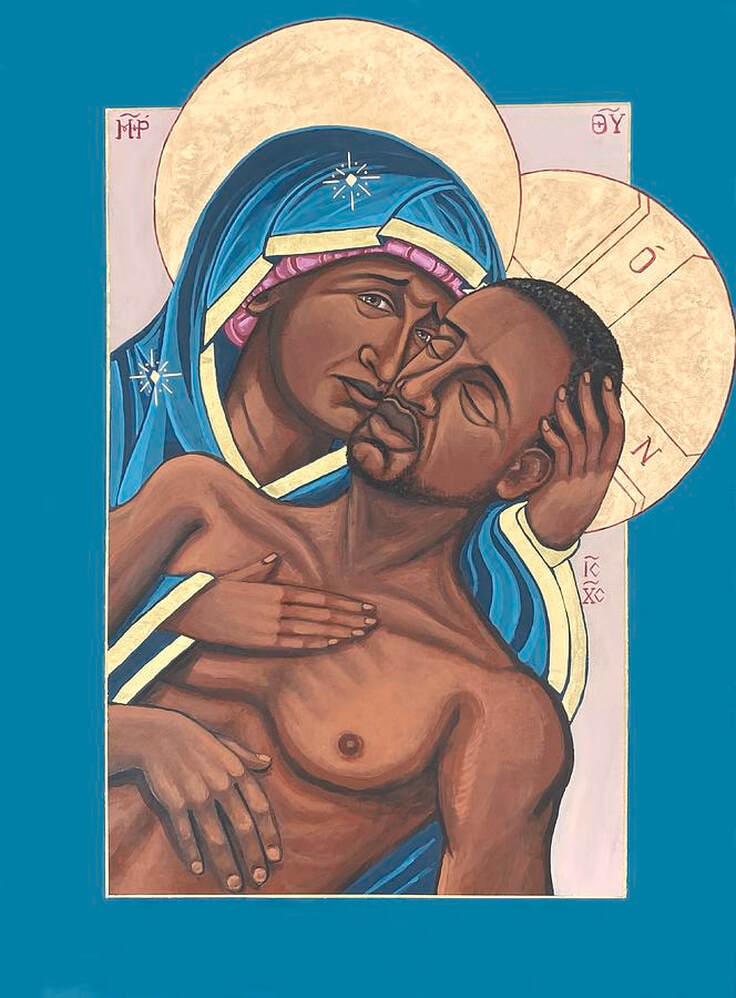

2020 was an apocalyptic year, a year of revelation. Amidst pandemic and protest, the deep seeds of racism and white supremacy were exposed in ways that captured our attention. The brutal violence white people’s privilege had distanced them from now played over and over on screens. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder that catalyzed demonstrations all across our nation, it was increasingly difficult to believe that racism was a part of our ugly past.[8] Though this was nothing new for black, latinx, or asian american communities, many white folks awakened to the systemic and persistent evil of white supremacy. This was a time of grief, outrage, and protest amidst the tide of police brutality against black and brown bodies. The prophets cried out, “I can’t breathe.” [9]

You can be sure that God heard their cries. For our God is a God on the side of the oppressed — those who are crushed, degraded, humiliated, exploited, impoverished, defrauded, and enslaved. Yet what was the response of God’s people? Did the Church hear their cries?

Many did not. Many chose to stay clear of the “politics” of the day in a Christ Against Culture stance. Others became even more entrenched in the particular ideology of their political party both right and left, unwilling to converse with the “other” in a Christ Of Culture approach. The polarizing divides were profound — splitting apart families, friends, and churches.

Similar to previous times of civil unrest, there was “the appalling silence of the good people” within the white church, who professed their love for all lives, denied their culpability, and proved to be a “great stumbling block in the stride toward freedom.” [10] There was a refusal to see, let alone address, the systemic nature of racism, resorting once again to a gospel that sanctions the personal over the social. The roots of this bifurcation go back to our country’s inception in the doctrine of the "spirituality of the church." This spirituality attempted to extricate the church from addressing the social evils of slavery, promoting a “Christianity [that] could save one’s soul but not break one’s chains.” [11] Yet, this hideous distortion of the gospel repeats in response to the outcries to value black lives. “Where were the saints trying to change the social order, not just to minister to the slaves [oppressed communities], but to do away with slavery [the systems that brutalize and oppress communities]?” [12] Who was listening to the black and brown prophets of the day?

Fortunately, there is a remnant of Christians who believe that Christ Transforms Culture in the sociopolitical sphere. Those who were willing to repent of America’s greatest sin, white supremacy, offering more than “thoughts and prayers.” They listened deeply to a perspective that contradicted their own. They learned a hard and grievous history. They stood in solidarity with the oppressed in protests and vigils. They followed the prophetic witness of African American, Native American, Asian American, and Latinx theologians and church leaders, engaging in civil action. They spoke out against white supremacy in their pulpits and among their peers not without cost, insisting that all created in the divine image share in equity and justice. They wrestled profoundly and lamented their complicity, beginning to find ways to take up the cause of the oppressed, amplify marginalized voices, and elevate black lives.

Yet Christians today must commit to the long, hard road of a lived repentance, “for our conversion to the Lord implies this conversion to our neighbor” — a radical transformation where we come to know “Christ present in exploited and oppressed persons.” [13] “We are not to stand around, hands folded, waiting for shalom to arrive. We are workers in God’s cause,” [14] joining the Spirit’s work of peace-making, justice, and liberation on the earth.

by Jessica Ketola

[1] Nicholas Wolterstorff, “For Justice with Shalom”, in Until Justice and Peace Embrace: The Kuyper Lectures for 1981 (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983), 72.

[2] Reinhold Niebuhr, “Types of Christian Ethics,” In Authentic Transformation: A New Vision of Christ and Culture, Glen H. Stassen, Diane M. Yeager, and John Howard Yoder (Nashville: Abingdon, 1996), 15-29.

[3] Donald W. Dayton, Rediscovering an Evangelical Heritage (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2014), 200.

[4] Matthew 5:13, Isaiah 58: 6-7, 12

[5] Karen Lebacqz, “Implications for a Theory of Justice,” in From Christ to the World: Readings in Christian Ethics, eds. Wayne Boulton, Thomas Kennedy, and Allen Verhey (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 257.

[6] Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” The Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr, 1963, 1.

[7] Gustavo Gutiérrez, “Liberating Spirituality,” in Spiritual Writings (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2011), 49.

[8] “‘I Can’t Breathe’: The Refrain That Reignited a Movement,” Amnesty International, June 30, 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/06/i-cant-breathe-refrain-reignited-movement.

[9] Jessica Ketola, “A Time of Reckoning, Revelation, Repentance, and Reformation: The Epiphany of America’s Greatest Sin,” Medium, January 12, 2021, https://medium.com/interfaith-now/a-time-of-reckoning-revelation-repentance-and-reformation-7003c588875b.

[10] King, Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” 4.

[11] Jemar Tisby, The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019), 38.

[12] Kathleen Jorden, “The Nonviolence of Dorothy Day,” in From Christ to the World: Readings in Christian Ethics, eds. Wayne Boulton, Thomas Kennedy, and Allen Verhey (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 443.

[13] Gutiérrez, “Liberating Spirituality,” 48.

[14] Wolterstorff, “For Justice with Shalom,” 72.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed